Canada’s retreat from digital services tax sparks questions over future of other online policies

Regulatory | |July 8, 2025

Canada’s decision to scrap its digital services tax (DST) has raised questions among political scientists and internet governance experts about the durability of the country’s other digital policy measures, such as the Online Streaming Act, Online News Act, and pending online harms legislation.

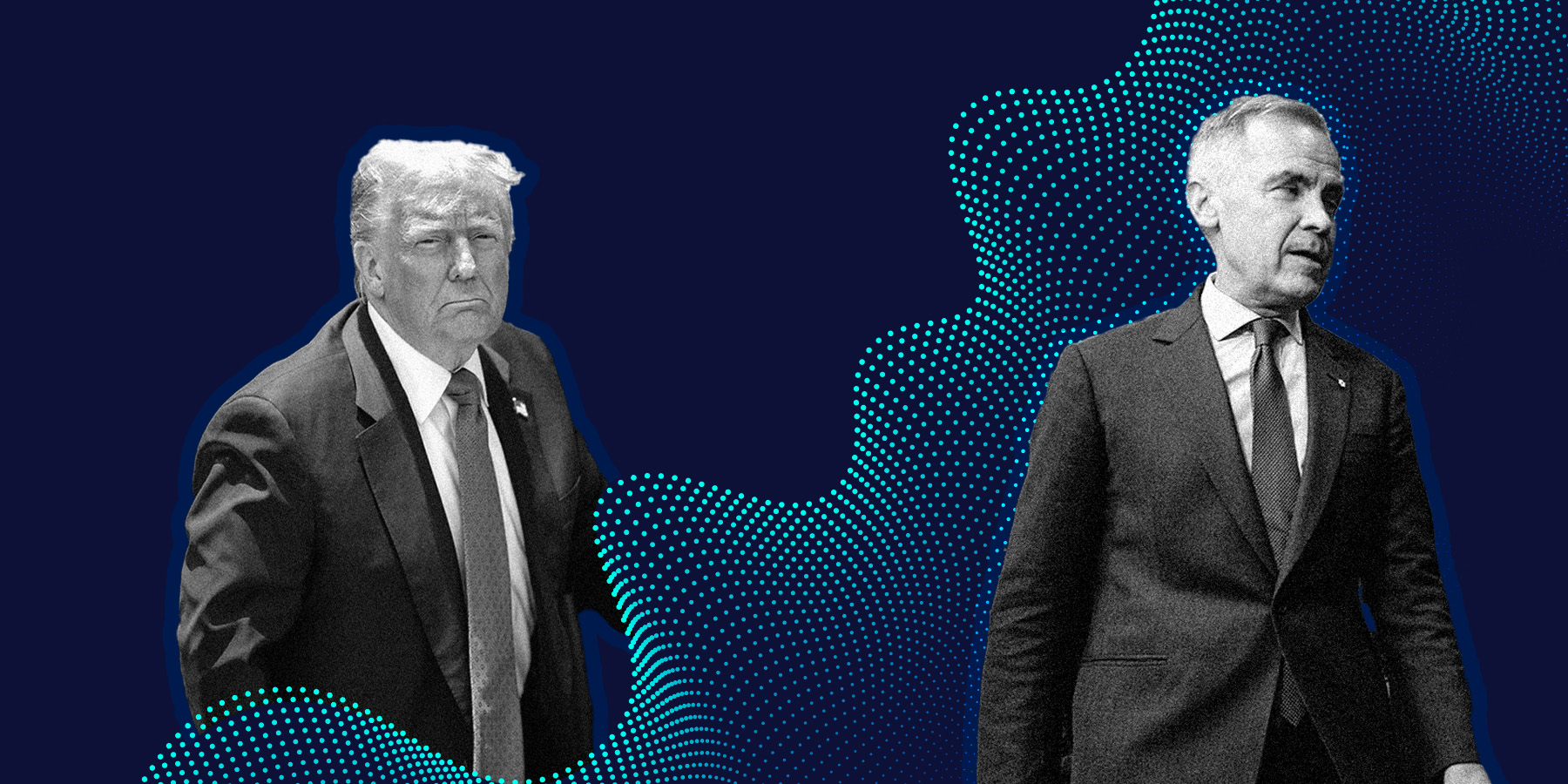

The federal government announced last week, a day before payment was due, that it would not be moving forward with the DST. The tax, which would have applied a three per cent levy on large multinational tech giants, had faced strong opposition from U.S. lawmakers and lobbyists who called it discriminatory and unfair. The walk-back revived trade talks between Canada and the United States, which were stalled by U.S. President Donald Trump days earlier after he called the “egregious” tax a “direct and blatant attack” on the U.S.

With the DST now dropped, some industry observers are concerned that other digital policies that carry financial implications for U.S. tech companies could be in the crosshairs.

‘Not surprising’ DST would be sacrificed, professor says

“It’s bad news,” said Carleton University journalism professor Dwayne Winseck of the decision to drop the DST in an interview with The Wire Report.

“I can see why the government would do this. Within the overall framework of a general trade and security agreement,” it is “not surprising” that it would be sacrificed, he acknowledged.

However, “this is a bad lesson,” Winseck continued, noting that the Trump administration now has both a “licence and inclination to use the heavy hammer” to pick off policies that might irritate it.

Blayne Haggart, a political science professor at Brock University, took it further, describing the move as “absolutely absurd” and a “very foolish move on the Prime Minister’s part.”

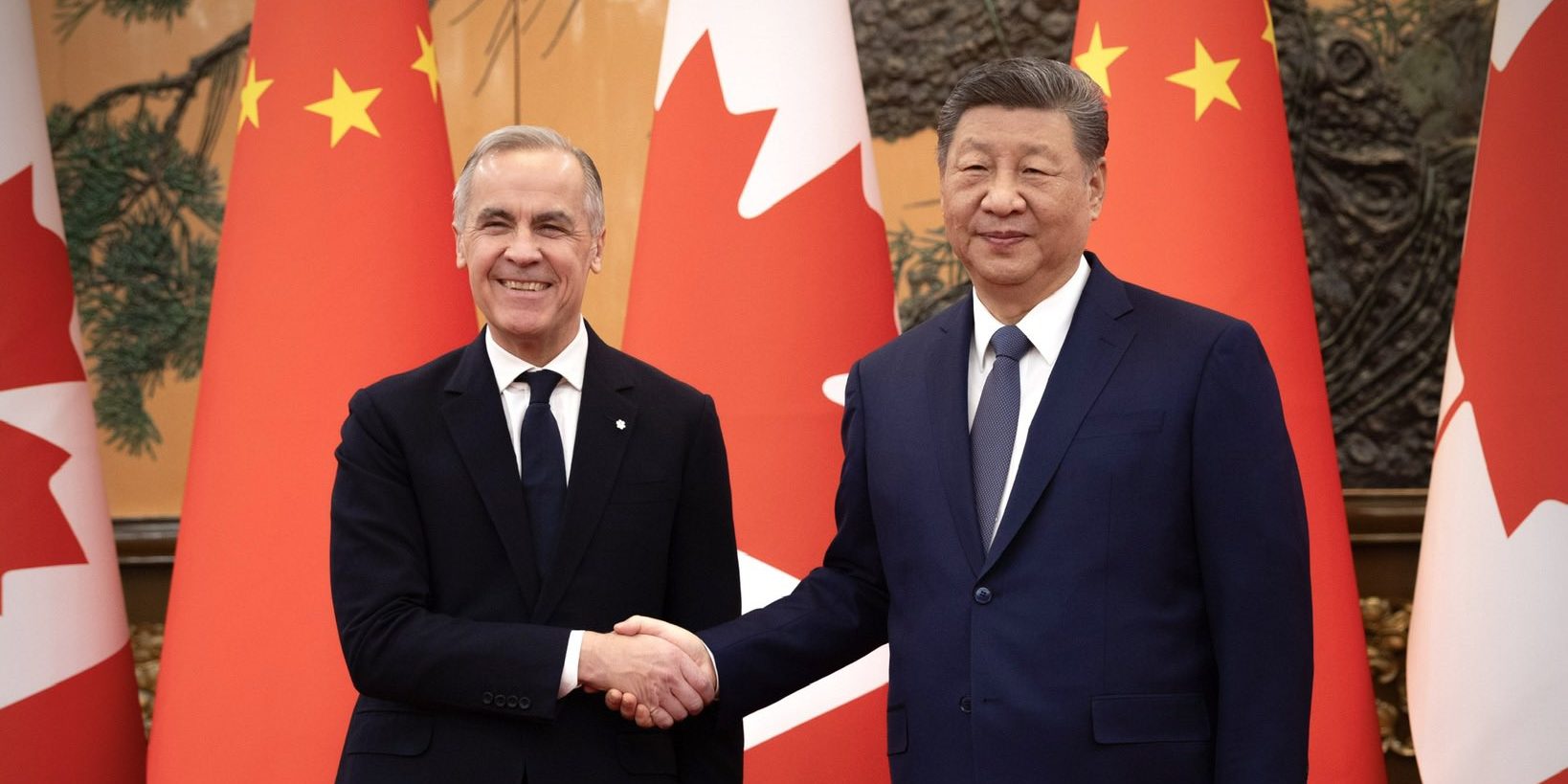

“Mark Carney has decided that it is a good idea to negotiate a comprehensive trade and security agreement with an untrustworthy partner, which itself is a huge problem,” Haggart said, emphasizing that the reason these negotiations are happening “is because Donald Trump ripped up the USMCA [United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement] in the first place.”

He said Trump has made it clear the U.S. is “no longer a trustworthy negotiator.”

“What this means is that we could give Donald Trump and the United States everything that they ask for, but it won’t buy us anything, because the United States can always change its mind, and they’ve shown very much a willingness to do that.”

Haggart warned that the U.S. administration could “change their mind” when another “irritant” appears in the relationship between the two countries. He noted that Canada’s DST is not a standout policy, pointing to similar measures in other countries.

“This isn’t really a tech story,” the professor stated, “it’s only a tech story because those are the interests that are dominant in the United States right now.”

“People think that annexation is just about armies marching across the border, but if you basically give the United States a veto over your policies, then you don’t have a country,” Haggart said.

Winseck shared Haggart’s concerns.

“Sovereign countries have to have the capacity to make their own laws that are going to govern commercial, communication, and cultural exchange. We cannot give up on these things and still call ourselves a sovereign country,” he said.

Other Canadian digital policies flagged as concerns in U.S.

The U.S. Trade Representative’s (USTR) most recent National Trade Estimate report on foreign trade barriers flagged the DST, Online News Act, and Online Streaming Act as areas of concern. While only the DST has so far prompted a retaliatory threat, Winseck said the report “really put a target on the back of Canada’s digital policies,” which were “all singled out.”

One organization pushing those efforts is the Computer and Communications Industry Association (CCIA), a Washington-based group representing major U.S. tech companies including Amazon.com Inc., Apple Inc., Alphabet Inc.‘s Google, Meta Platforms Inc., and Intel Corp.

The CCIA has been vocal in its opposition to a number of regulatory measures around the world, including Canada’s Online News Act and the Online Streaming Act, arguing they violate international trade agreements and unfairly target U.S. firms. The group was also strongly against legislation that Canada was considering during the previous Parliamentary session that would have introduced AI regulations and updated the country’s privacy laws. It pleaded for a “firm response” from the USTR.

Michael Geist, Canada research chair in internet and e-commerce law at the University of Ottawa, said those challenges could intensify depending on how aggressively Canadian regulators enforce the new laws.

“Whether or not there will be a parallel in terms of the U.S. government becoming more actively engaged on some of those other issues…it remains to be seen,” he said in an interview with The Wire Report, but he acknowledged that the USTR report shows they are on their radar.

When it comes to streaming regulations, “if we end up with the CRTC ruling that there are significant new fees required to be paid and some of those same U.S. companies are not even eligible to qualify for the funds that result, I think it’s certainly possible we could see this escalate as a trade issue,” said Geist.

Mackenzie Porter, a political science PhD candidate at McMaster University, has been conducting research for TheTechLobby, which examines various tech companies’ lobbying activity to the Canadian federal government. She conducted a case study on the DST with McMaster political science professor Tony Porter (unrelated).

In Canada, “there wasn’t a whole lot of lobbying on behalf of these firms,” said Mackenzie Porter in an interview with The Wire Report. However, she did note an unusual alignment between the corporations and the U.S. state, considering the recent wave of antitrust cases against big tech.

“In this instance with the DST, [those differences] kind of got pushed aside, and now they’ve kind of aligned together in order to work to make sure that the money, the tax revenues, aren’t being pushed to other countries.”

Tony Porter said the DST’s retroactive application and financial impact probably made it a top priority for both big tech companies and the Trump administration.

“I would think it would be a higher priority to push back against digital services tax issues than the other digital issues that are of great concern in Canada, like the Online Streaming Act, the Online News Act, and the online harms act.”

The researchers said they agree that Canada is entering a more tumultuous phase of digital policy enforcement.

For Haggart, the implications are deeper than policy.

“We still need to have that very honest conversation about what it means to be a small country, kind of all alone in North America, next to a superpower that basically no longer respects sovereignty or the rule of law.”

Haggart said it is difficult to answer to such an existential question, but suggested that the Canadian government should be working closer with the European Union, Australia, Brazil, and others to come up with “digital policies that rhyme with each other, because that’s the only way we’ll be able to counter the United States.”

“If we’re isolated, we’re going to fall, so we need allies, we need friends, and we need to be part of bigger things. That starts with coordination and cooperation — and creativity, too.”